Uranium Mining in

the Navajo Nation

In 1946, President Truman created the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to oversee nuclear projects. The AEC identified the Navajo reservation as a potential source of uranium. Since Navajo lands were held in trust, mining companies could easily access the deposits. Moreover, the government saw the Diné as a vulnerable population to exploit; they had high rates of poverty, faced language barriers, and lacked basic resources.

Monument #2 Mine miners posing at the mine entrance, 1950-1959, Colorado Plateau Archives

Navajo miners near Cameron, Arizona, 1956, Utco Uranium Corporation

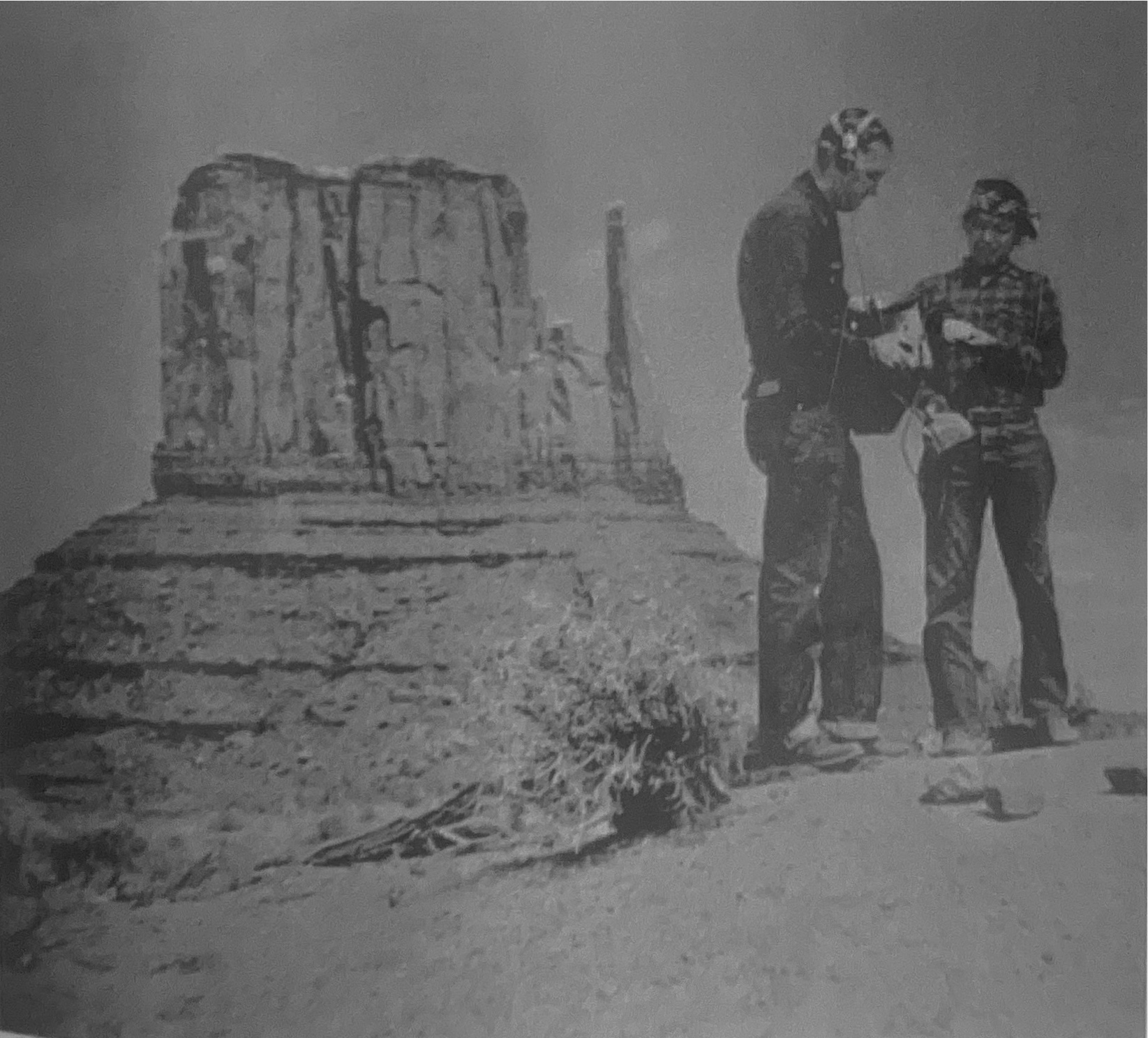

Some Diné people jumped at the economic opportunity without comprehending the cost of their motherland’s decimation. With lent Geiger counters, Diné families went on expeditions to search for uranium.

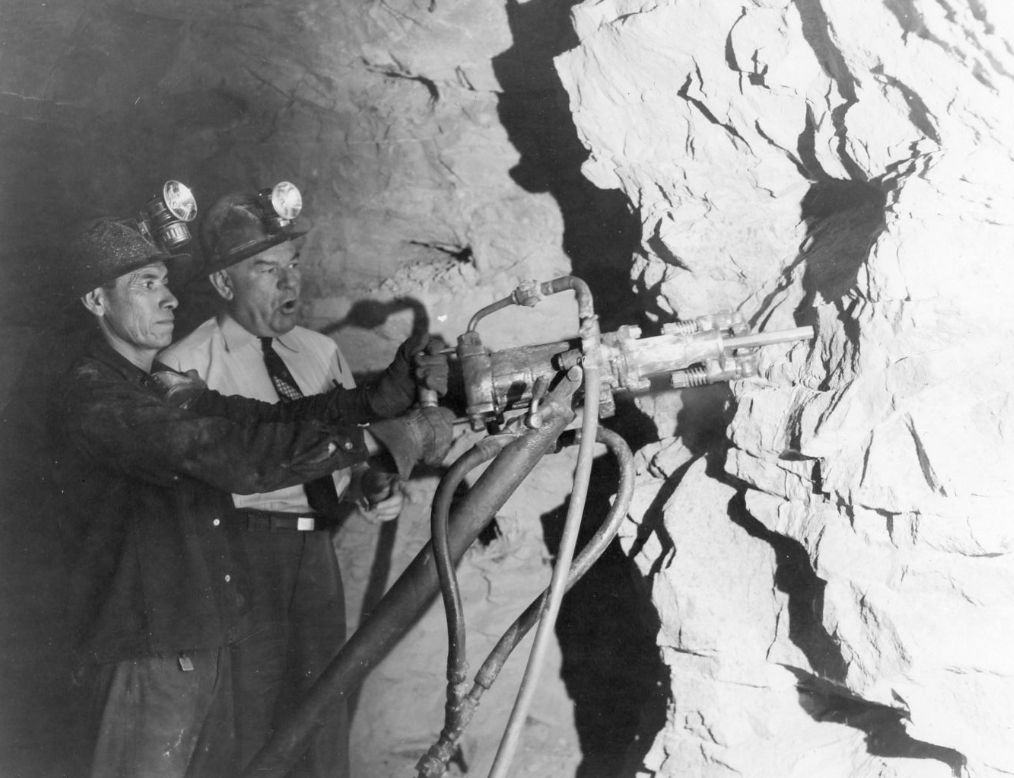

Dennis Ward Viles with a miner drilling for carnotite ore in the underground tunnel at the Monument #2 Mine, 1950-1959, Vanadium Corporation of America

Indian trader Harry Goulding showing a Navajo uranium prospector how to use a Geiger counter, 1950s, Popular Mechanics

As the mining began, the Public Health Service (PHS) launched studies on the Diné miners to record the health effects of radiation exposure. Published in 1980, one 1950s study found that of 150 miners in Shiprock, New Mexico, 133 died of lung cancer or fibrosis. Another study reported radiation levels 90 times above acceptable parameters. Researchers deliberately withheld findings from the miners, fearing disruptions to uranium production. The PHS silently watched—offering no warnings, no protection, and no restitution.

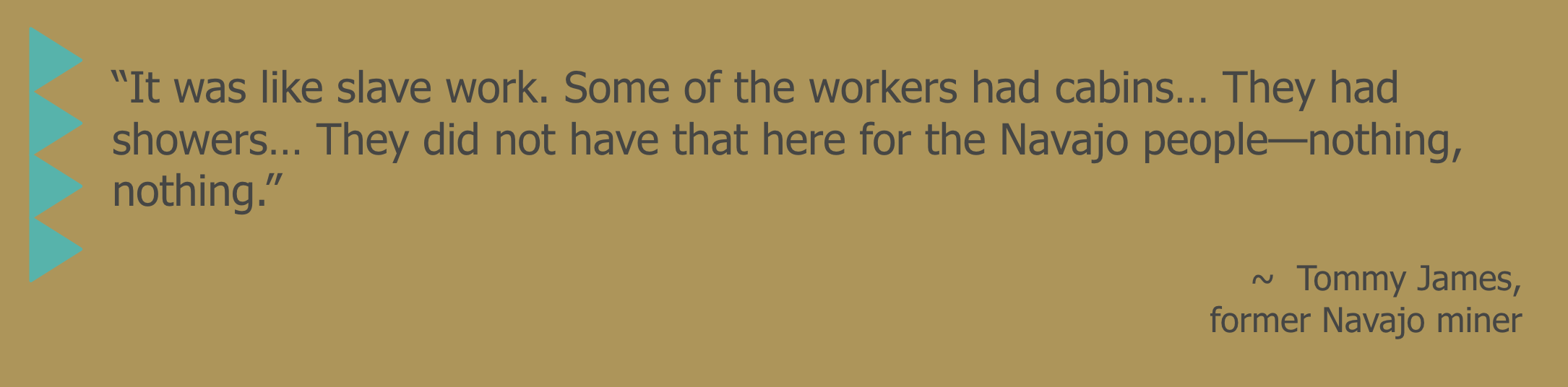

Unlike white miners, Diné workers labored in poorly ventilated mines without protective equipment or safety measures. Mining company supervisors reprimanded those with moral reservations, reminding them of their patriotic duty and the economic prosperity promised to the Navajo Nation.

Monument Valley, 1948-1966, Vanadium Corporation of America

Carnotite mining operation in Monument Valley, Arizona, 1950-1959, Vanadium Corporation of America

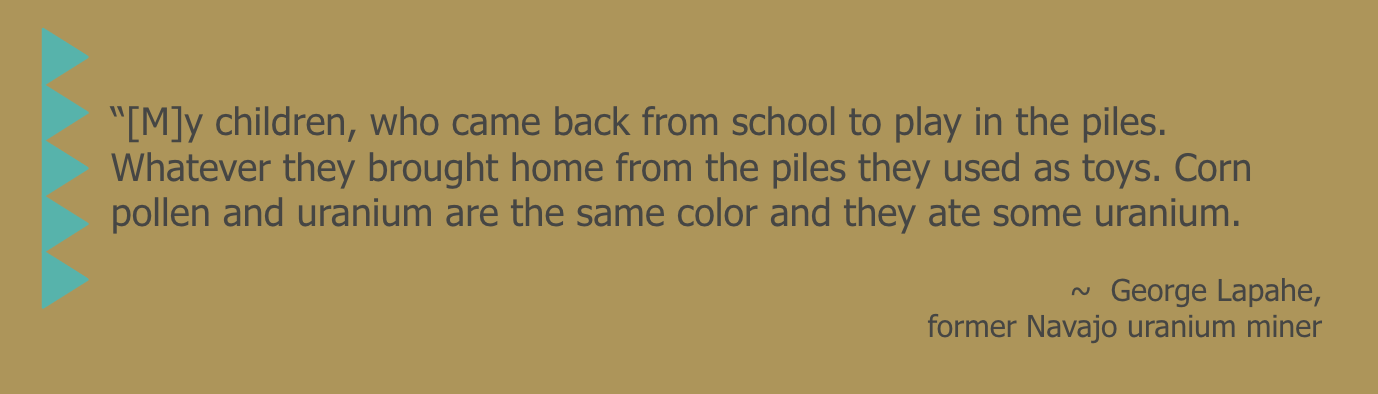

Miners’ families were also affected by the mining. Children enjoyed molding the yellow dirt into animals and lighting it on fire, as their fathers did. Families drank and cooked with water from the polluted streams. When miners returned home, their wives had to clean their clothing dotted with uranium.

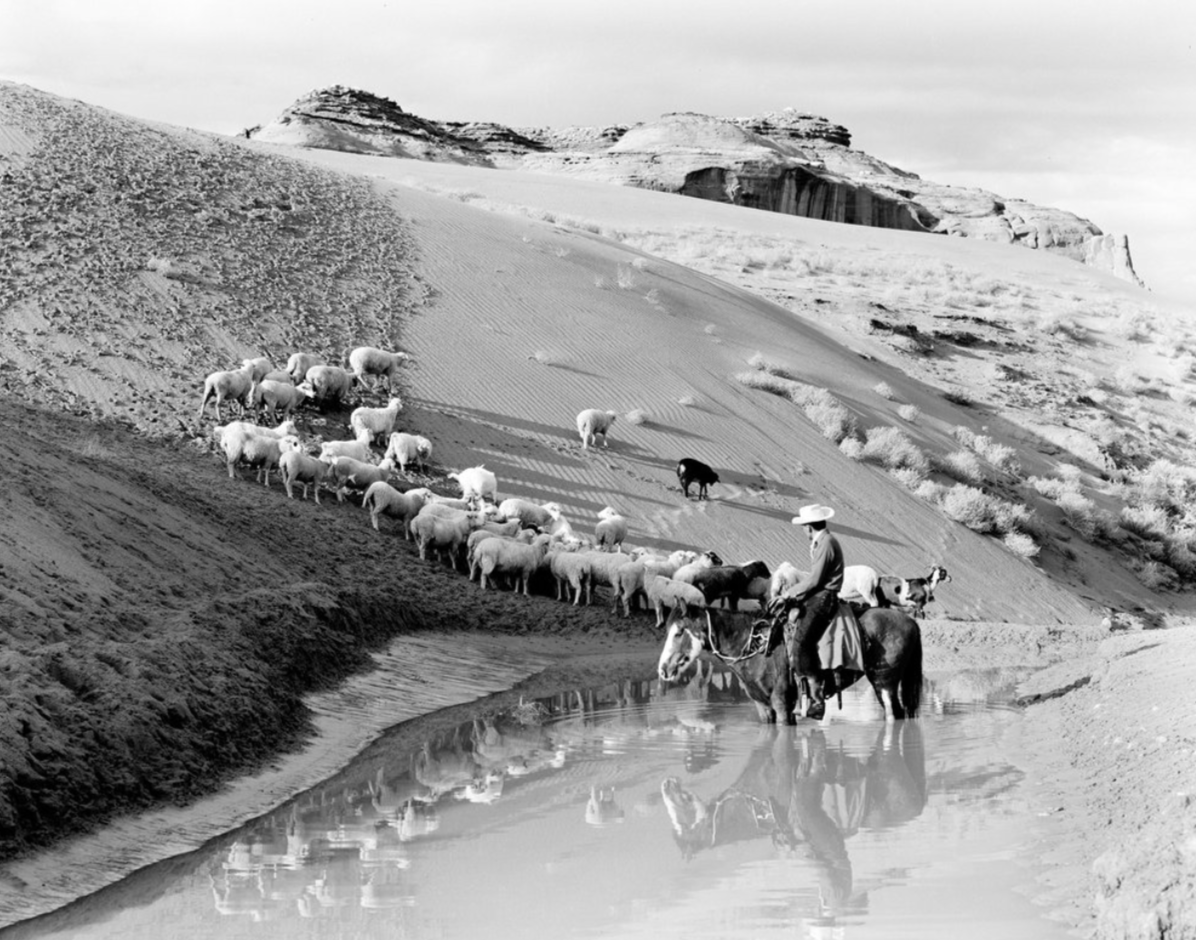

Monument Valley- Sheep at Sandspring + Indian, 1950-1970, Josef Muench

Lois Neztsosie quenching her thirst at a natural spring, 1960s, Los Angeles Times

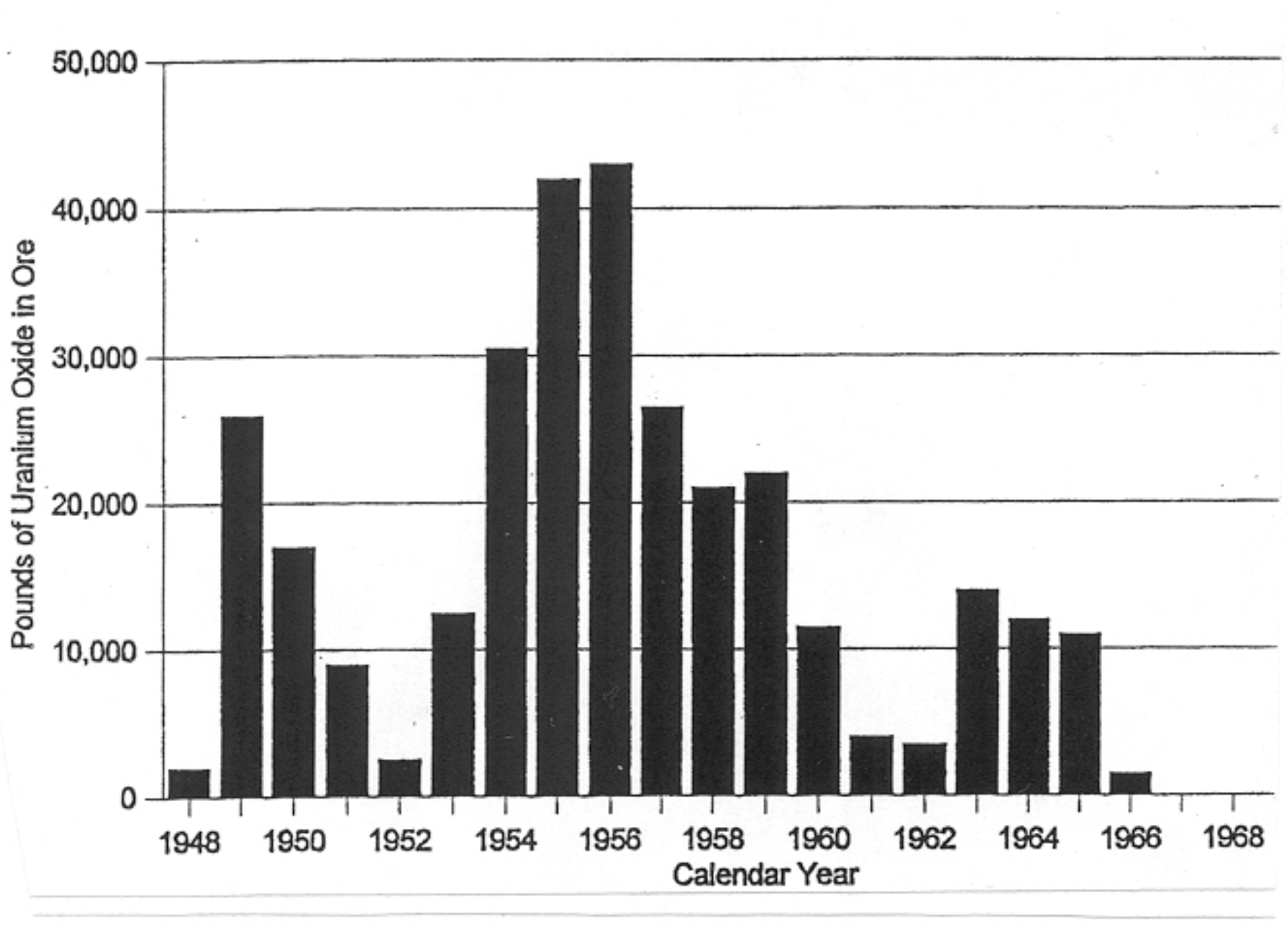

After mining companies depleted the land of its natural resources, they abandoned the mines and left behind radioactive waste. Despite producing 30 million tons of uranium that helped secure U.S. victory in World War II, the Diné received no compensation for their contributions.

Uranium production in the Navajo Nation, Northern and Western Carrizo Mountains, 1999, Clark University

Dooda Leetso The Legacy of Navajo Nation Uranium, 2015, Colorado Plateau Foundation